2012 saw a turning point in FE observations (perhaps similarly in schools?) Under the common inspection framework for FE and skills there was a huge shift from observing what the teacher was doing to observing what the learners were doing – learner/learning focused observations.

I remember it vividly, the internal observation process (which was graded), had previously graded the teaching and the learning as two separate grades, but as a result of Ofsted changes, moved to a single grade -one that was purely ‘learning focused’. Surely this was a positive thing? Our intuition would tell us that focusing on the learners is far more productive than focusing on what the teacher is doing. After all, the teacher might be an imaginative, engaging presenter of information, but if the learners aren’t doing anything, then they’re not necessarily learning. Watching what the learners do allows one to make more informed judgements on the ‘learning’ in the session, regardless of grading or not… or does it?

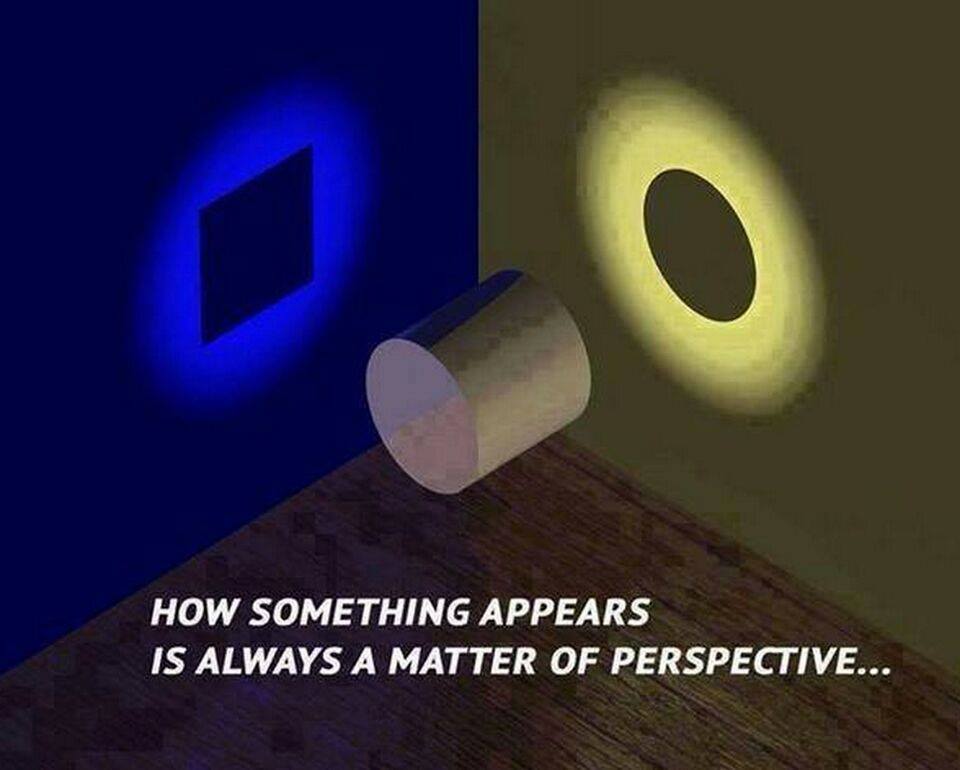

Whether graded, or ungraded, I think lesson observation in its current guise (judgement based) is here to stay. Neoliberalism is the current policy model, thus accountability is a driving force and therefore, teaching and learning quality processes and Initial Teacher Training programmes will probably use judgement based observations. After some thought, I’m starting to wonder whether lesson observation that focuses purely on the learner is more counterproductive than beneficial and that we perhaps need to view things from a different perspective. Let me explain why:

1. Like it or not, we can’t actually see learning in the lessons.

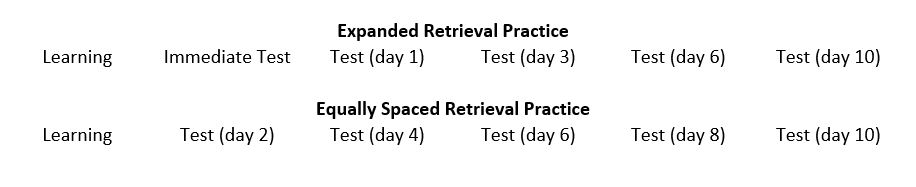

However one defines learning, it must encompass a change in behaviour/ knowledge/ understanding/ ability and be relatively permanent i.e. a long term change. How can we see this in isolated sessions? In short, we can’t. Soderstrom and Bjork have extensively reviewed the distinction between learning and performance, finding:

‘During the instruction or training process … what we can observe and measure is performance, which is often an unreliable index of whether the relatively long-term changes that constitute learning have taken place’.

This is not to say that learning isn’t taking place when we observe performance, but essentially they argue that there can be learning without performance and that there can be performance without learning. So with this in mind, should we place so much emphasis in how the learners are ‘performing’?

2. Learning is a long and slow process.

Whilst this may not be attractive to the consumer culture we have in education, it is a matter of fact that practice is essential to master skills and develop automaticity. Ericsson et al argue that:

‘argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain’

So with this in mind, lessons may at time appear boring and learners may appear uninterested in their learning. Does this mean that they’re not learning though? Let’s explore what Rob Coe has deemed as poor proxies for learning based on extensive research:

‘Poor Proxies for Learning (Easily observed, but not really about learning) 1. Students are busy: lots of work is done (especially written work) 2. Students are engaged, interested, motivated 3. Students are getting attention: feedback, explanations 4. Classroom is ordered, calm, under control 5. Curriculum has been ‘covered’ (ie presented to students in some form) 6. (At least some) students have supplied correct answers (whether or not they really understood them or could reproduce them independently)’.

With this in mind, what are we able to ‘see’ in an observation that really provides us with objective evidence of learning? Not much.

3. We learn better when we face difficulties with learning.

Again, this supports the notion above. Coe informs us that ‘learning happens when people have to think hard’. Many learners just don’t like hard work, so teachers often result to ‘fun’, learner led lessons in an attempt to motivate learners. Fun lessons may be great to observe, but if the content is easy, or the learners are investing more of their efforts thinking about the colouring in of a poster than the content they’re putting on it, then we have a problem. In Coe’s excellent ‘Improving Education‘ publication this information about Nuthall’s study really highlights the problems we have in education currently.

Students may not necessarily have real learning at the top of their agenda. For example, Nuthall (2005) reports a study in which most students “were thinking about how to get finished quickly or how to get the answer with the least possible effort”. If given the choice between copying out a set of correct answers, with no effort, but no understanding of how to get them, and having to think hard to derive their own answers, check them, correct them and try to develop their own understanding of the underlying logic behind them, how many students would freely choose the latter? And yet, by choosing the former, they are effectively saying, ‘I am not interested in learning.’

So my point here is that looks can be deceiving when observing learners in the session and that what we think might appear to be good learning, might not be most beneficial to the learners.

4. Learners don’t always know what they need to know.

I think learner voice is often over-valued in education. I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t listen to our learners, but if they don’t enjoy a lesson, it doesn’t mean they’ve not learnt anything. Conversely, when they’ve had great fun in a session, it doesn’t mean that they have learnt something. Within each subject there are key features that must be learnt in order to access other things, but by focusing too much on engaging learners by giving them autonomy over how/what they learn in order to motivate them, we might actually be hindering learning (see previous posts on instructional design here and here)

5. Insufficient knowledge of subject area.

Often those observing are not subject experts and therefore, despite focusing on the ‘learning’, have no real understanding of the stage and level that learners should be at with subject content, nor do they have an understanding of content, therefore judgements on ‘learning’ are highly contentious.

6. Insufficient knowledge of effective study strategies.

With all due respect, there are some individuals that observe and give feedback to teachers, where they themselves have insufficient knowledge and understanding of effective study strategies, so feedback is likely to be inaccurate and instead focus on things that are ‘in-vogue’. For example, the ‘all, most, some’ lesson objective that flashed in the pan a few years back, or the infamous learning styles/preferences that continue to linger in education.

Initial thoughts for solutions

1. Should we focus more on what the teacher is doing, in addition to what learners are doing?

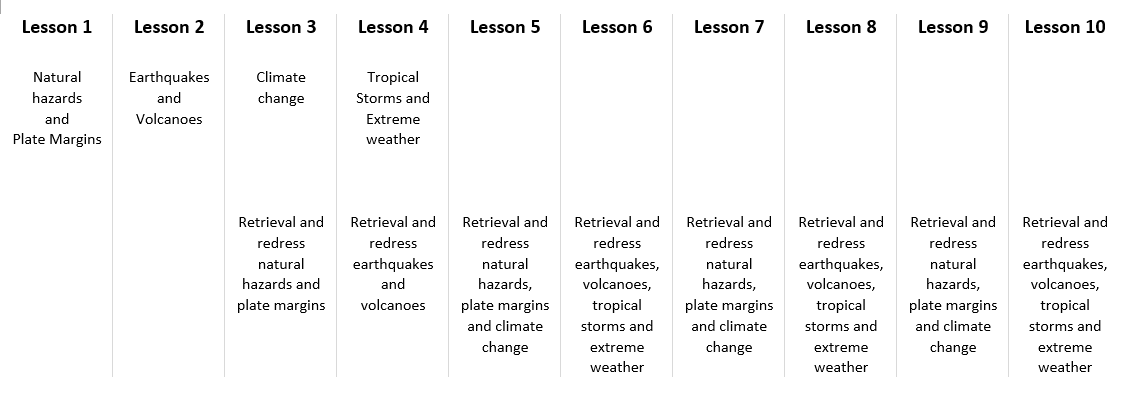

If effective learning strategies are being used, but the learners are not observably making ‘progress’, then is this a problem? For example, if a teacher is providing instruction using dual coding and chunking information, but learners are just listening to them, focusing on the learner isn’t going to reveal much. Or, if the learners are working together to grapple with a challenging problem and not able to do it during the observed time, focusing on the learner isn’t going to reveal much. Or, if the class is being tested on prior knowledge, but few get the answers correct, focusing on the learner isn’t going to reveal much. Sure, it is expected that with these examples, there will be teacher intervention to support learner progress, but what if they just don’t get it in that session? All of the strategies used are desirable for improving long term memory (sure, learning isn’t just about this).

2.Should learning be judged or discussed based upon what learners know/understand as a result of their lessons to date, not the session being observed?

In this situation, the observer would ideally be a subject expert, so that they know what stage learners should be at and using evidence from discussions with the teacher and learners, examining previously assessed work, success rates and the stage that learners are at in the learning. A collection of evidence might be synthesised following several observations conducted with the same class over the year and judgements made on teaching and learning by using a variety of data.

3. Should we give the teacher an opportunity to watch themselves and form their own judgements about teaching and learning?

This approach allows the teacher to have ownership of the process and self-assess against whichever standards are being used. Through the work of Wiliam, it is clear that self-assessment against clear success criteria is highly effective in improving achievement for learners, so why wouldn’t it have the same effect for teachers?

4. Should we just remove ‘judgements’ altogether and instead focus on our evidence based practice through communities of practice?

Indeed, through non-judgemental peer observations, the nature of observation could be flipped on its head. This blog post suggests an approach for using observation as an opportunity for the observer to be developed, rather than the teacher, with no judgements, merely dialogue centred around the lesson. Matt O’Leary (2013) tells us that a ‘performance driven focus [which] has culminated in a prescribed and codified model of what it means to be an effective teaching professional…with limited opportunities for the use of observation to stimulate collaborative discussion about the process of teaching and learning’, so why not create the space for this in communities of practice?

I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on observation.